Kate Pincus-Whitney loves paint. And Los Angeles. And food. These are three things you’ll learn quickly by speaking with her, but her paintings tell you everything you need to know.

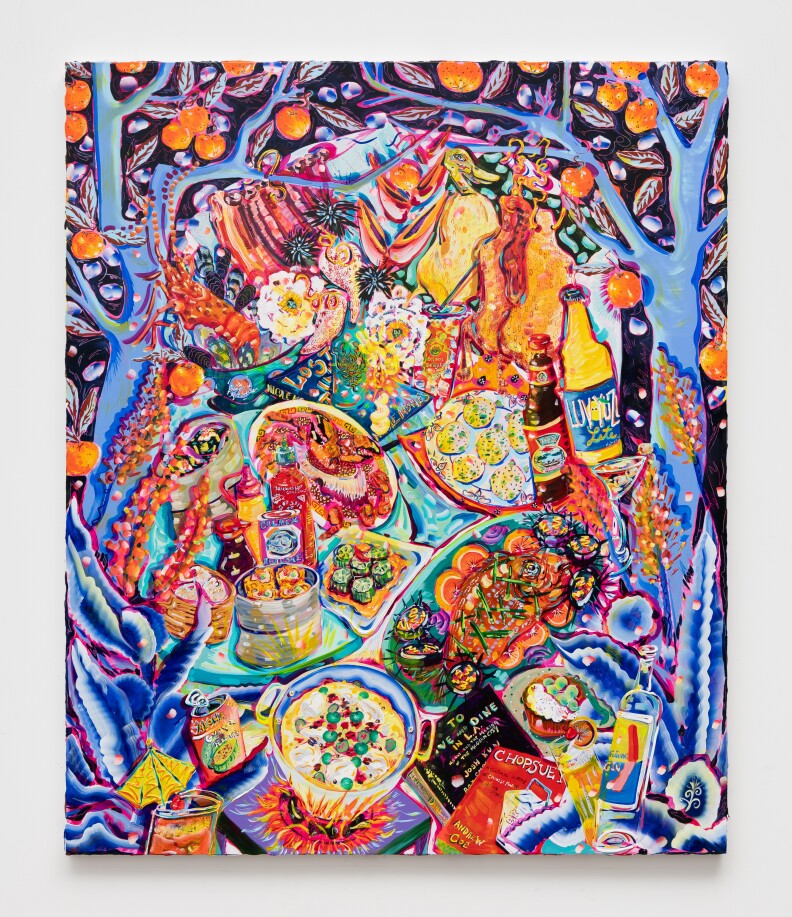

An acrylic tablescape

Large scale, textured and layered with food, objects and history, the pieces for the artist’s first solo show “To Live and Dine in LA/You Taste Like Home” are portals made of acrylic paint. They let viewers into a world where martini glasses wiggle and the squiggle of cream on top of stuffed celery from Musso and Frank’s leaps off the canvas.

On her tables, all of L.A. history sits together. “[California] is five, seven million different narratives going on all at the same time,” Pincus-Whitney says, “and they’re all intertwined, and the most basic aspect of it all is to eat.”

The pieces now hang in the Anat Ebgi gallery on Wilshire Boulevard and are on view through Aug. 17. I was able to get a sneak peek for this article a few weeks ago, meeting Pincus-Whitney while she prepped for the show in her Downtown L.A. fashion district studio — an airy space with floor to ceiling windows that she shares with her husband, who’s also a visual artist.

One of Pincus-Whitney’s paintings next to a cart of art supplies in her studio.

“When I’m starting a painting, I first make what I call my theater,” Pincus-Whitney says. She creates something akin to a proscenium arch with strokes of flora and fauna she lays around the edge of the canvas. Birds of paradise, palm fronds, orange tree branches and more give way to the tablescapes beneath, “where you’re like a little nymph coming in through the greenery.”

Pincus-Whitney is stereo blind, meaning she doesn’t perceive depth in a traditional way. She uses shadows and greenery to create a frame that lets a viewer feel like they’re both looking above the table and falling into it.

Through this frame, Pincus-Whitney is transforming the familiar, placing everything from your neighborhood hot-pot place to the grand neon signs of Hollywood onto a table together. There’s even a reference to painter Ed Ruscha’s 1964 piece “Norm’s, La Cienega, On Fire”

A detail shot of Pincus-Whitney’s painting “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood”

A grandmother’s influence

Pincus-Whitney was born in Santa Monica and raised by her mother and grandmother in Santa Barbara. She returned to L.A. after the pandemic in 2020. She and her now-husband, then-boyfriend, were finishing graduate school in Rhode Island when the shut downs began. That’s what prompted the move back West, Pincus-Whitney says, remembering the moment of realization: “I’m not gonna die in a place filled with khaki pants. I miss California so much.”

L.A., food and family go hand in hand for Pincus-Whitney. Her grandmother fell in love with food after discovering Julia Child, and was an “incredible cook” who stoked Pincus-Whitney’s curiosity. They’d go to Italian and Mexican markets together, cook Cantonese food, or drive three hours from Santa Barbara to the Valley for dim sum, a memory captured in the layers of her first tablescape painting, “High Holy Har Gow Winter Pilgrimage.”

Pincus-Whitney made the piece in 2020 as a shrine to her grandmother on the 10-year anniversary of her death.

Pincus-Whitney’s painting “High Holy Har Gow Winter Pilgrimage”

A love of LA neighborhoods, and family

Once an anthropology major, Pincus-Whitney describes herself as “this little weird artist anthropologist, running around the city, tasting things, smelling things, looking at things and, like, trying to understand or unpack the identity of this place.”

Part of that journey led her to the L.A. Public Library, where she came across the book “To Live and Dine in L.A.” by Josh Kun. Though the book includes essays by critics and chefs like Jonathan Gold and Roy Choi, the biggest draw for Pincus-Whitney was the archive of vintage menus from L.A. restaurants and the exploration of how cultures and food intermixed — the rich L.A. history that unfolds neighborhood by neighborhood and restaurant by restaurant.

Pincus-Whitney’s painting “Wednesday Farmers Market (From Tutti Fruiti to Pollan) or The Times They Are A’ Changing’.”

Since each painting for this series focuses on a different neighborhood and its food culture and restaurants, Pincus-Whitney is a font of L.A. restaurant names and recommendations. Everything West to East, from The Apple Pan to Jitlada to a nearby corner tamale vendor, Pincus-Whitney says “it’s so divine to go to a neighborhood that you’ve never been to and to walk on the streets and smell the different smells.”

But there’s also beauty in returning to the familiar.

“The Real McCoy,” a painting with references to Canter’s Deli, Musso and Frank’s, and Phillipe’s, also includes homages to Pincus-Whitney’s family, and their lives in L.A. Her grandfather on her father’s side, John Whitney, wrote a pioneering textbook about computer graphics and animation. In the painting, she’s placed his work near a bottle of sauce from Phillipe’s, his favorite restaurant.

“He died when I was three,” says Pincus-Whitney. “I don’t remember him at all. But, I can go to Phillipe’s. I can order the lamb french dip sandwich, extra wet, with extra spicy mustard and blue cheese. And that was his favorite thing in the entire world. And I can learn about and taste him in that thing.”

Pincus-Whitney’s painting “The Real McCoy.”

On her mother’s side, her grandfather was Irving Pincus, a writer and producer perhaps best known for the TV show “The Real McCoys” in the 50s and 60s. He died before Pincus-Whitney could meet him, but she, alongside her mother and grandmother, could still go to Musso and Frank’s to order his favorite meal.

“It’s like you could touch one thing or taste one thing and it immediately transports you,” she says. In the painting, one of his scripts lies next to a plate of their sand dabs, his go-to.

A detail from the painting “The Real McCoy.”

“You don’t ever eat a meal that isn’t filled with history…that isn’t filled with somebody’s labor,” Pincus-Whitney says.

Whether that’s California’s indigenous and colonial history, agricultural history, the labor of farm workers, line cooks or family members, Pincus-Whitney is concerned with the layers of work and meaning behind every meal that might come across our tables.

Those histories are why L.A, a relatively young city, has such a rich, deep culinary scene. And they’re histories rife with tensions: exploitation, alongside culture and care.

Clearly moved, Pincus-Whitney says, “I really, genuinely believe that hope lies in sharing a meal with a stranger.”

“To Live and Dine in L.A./You Taste Like Home “is on view at the Anat Ebgi Gallery through Aug. 17.

Have An Idea For A Food Story?

Send it our way. We can’t reply to every query we receive but we will try to help. We’d love to hear from you.