LATE one afternoon, I walked across the north side of Trafalgar Square from St Martin-in-the-Fields. The flag on the National Gallery was at half-mast, but none of the staff seemed to know why.

A supervisor did not even know there was a flagpole; outside, when I pointed it out, on the pediment above the staff entrance to the gallery, he shrugged his shoulders and walked off. I went back into the gallery to the main information desk. Same story.

I later learned from the head of communications that it honoured the financier and former member of the Bullingdon Club Jacob Rothschild, who had died the previous day, aged 87. Lord Rothschild had been Chairman of the National Gallery 1985-91 and again 1992-98. Her message had not got to the gallery staff.

The Courtauld Institute, the Ashmolean Museum, the State Hermitage Museum of St Petersburg, and the Qatar Museums Authority also owe Lord Rothschild much; but his living monument is at Waddesdon Manor (NT), one of the famed Buckinghamshire houses that his family had built in the 19th century, custody of which he undertook more than 30 years ago as one of the Jewish stately homes of England.

He was extraordinarily generous, learned, and lively, and a businessman to be reckoned with. As an example of his philanthropy, he bought an Old Master painting that its aristocratic owners were flogging off and then loaned it back to the London house where the family had first displayed it when they brought it from Italy in 1768.

That picture, Guercino’s King David of 1651, sold at Christie’s in July 2010 for more than £5 million. In this exhibition, it is shown in the red Anteroom, alongside Lord Rothschild’s very last acquisitions, a much earlier painting (1618/19) by the same artist, Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (1591-1666), of Moses on Mount Sinai, his face ablaze with his encounter with YHWH (Exodus 34, 29 and 30) with hands that have hewn the replacement tablets of stone (Exodus 34, 1).

In Paris, in November 2022, the Moses appeared at auction with an estimate of €5000-6000, and was picked up as a “sleeper”, labelled “Bolognese ? follower of Guido Reni”, by Fabrizio Moretti for €590,000 before being sold to the Rothschild Foundation at Waddesdon.

From the Moses of his early years — before he moved from Bologna to Rome when his patron and fellow countryman Alessandro Ludovisi (1554-1623) became Pope Gregory XV in 1621 — to his 1651 work we see the development from the sketchier and brusque handling to a sinuous, almost feline, way of painting fabric.

The exhibition also includes paintings that he undertook in the same year as the Rothschild David. These each depict sibyls, the pagan prophetesses of post-classical times who allegedly foretold the coming of the Christ. All turban, billowing draperies, with scrolls and books, they would be indistinguishable without inscriptions to identify them. With some dozen sibyls, Guercino had a rich field.

The National Gallery’s Cumaean Sibyl with a Putto came from the late Sir Denis Mahon’s collection. As Europe’s leading historian of Guercino, his generous bequests have strengthened our knowledge of 17th-century Italian art. The sibyl was painted as a pendant to the David for a local Bolognese nobleman, Guiseppe Locatelli (1627-1711).

The seemingly unusual iconographic pairing derives from the Latin sequence Dies Irae:

Day of wrath and doom impending!

David’s word with Sibyl’s blending,

Heaven and earth in ashes ending!

Before the picture could be sent to Cesena, outside Bologna, Prince Mattias de’ Medici, brother of Ferdinand II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, gazumped him. Rather than paint a replica for the disappointed Locatelli, Guercino devised a new composition, painting instead The Samian Sibyl with a Putto (which was also acquired by the Spencers; National Gallery since 2012).

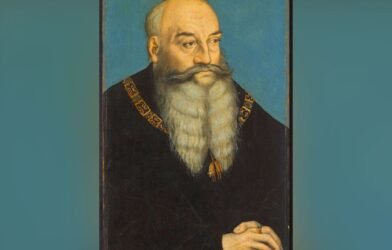

In the Red Anteroom at Waddesdon, the two sibyls hang either side of the King David, a painting that Lord Rothschild dubbed the “Boardroom portrait”. But it is more than that. David was a warrior king (who, like many financiers, could be ruthless), and he wears greaves over his sandals to remind us that he still had many battles to fight. He, too, has a turban, as if he were a Byzantine ruler or satrap.

The Libyan Sibyl (HM the King) was painted for Ippolito Cattani, who paid 150 scudi for it in December 1651 as a pendant to yet another painting of a sibyl. We have disturbed her reading, but she is so engrossed that she does not look up even for a moment. It is likely that the Libyan was bought for King George III in the early 1760s, a few years before Gavin Hamilton brokered the King David and the Samian Sibyl and had them framed by James “Athenian” Stuart for Spencer House.

Frustratingly, the original sibyl is hung lower that the David, making the wall of three pictures look uneven. Although the frame is very different from the neo-classical ones made for the Spencers, this is an unfortunate infelicity.

Given his prolific skills and the range of his religious and narrative scenes, it is good to be able to spend time in slow looking at five of Guercino’s masterpieces; if you want more sibyls, and you can to get to Turin, the Royal Museums there have a hundred of his works in the exhibition “Guercino: Il Mestiere del Pittore” (Sale Chiablese, museireali.beniculturali.it), which was due to close this weekend, but whose run has been extended to 15 September.

“Guercino at Waddesdon: King David and the Wise Women” is at Waddesdon Manor, near Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, until 20 October. Phone 01296 820414. waddesdon.org.uk